Zoho Corporation and ManageEngine’s event went beyond commemorating longevity; it framed three decades of growth as proof that a different kind of global software company can be built from India: privately held, product-led, deeply local, and unapologetically long-term in its thinking.

30 years on: A long-term bet that paid off

Opening the sessions, Shailesh Davey, Co-founder & CEO, Zoho Corporation, underscored that the group’s current global footprint of about 20 data centres and 30 offices is the result of patient, compounding decisions rather than rapid-fire expansion. He reminded attendees that Zoho started offering cloud services as early as 2006, even before hyperscale providers entered the market, specifically so the company could build deep operational expertise and “pass on the benefits to the customer” instead of depending on third parties. That expertise, he noted, now extends far beyond software into areas such as running data centres, canteens, and even bakeries—deliberate choices that reflect a long-term view of value creation and self-reliance.

Davey also tied Zoho’s philosophy of “transnational localism” to its physical and talent footprint: senior leaders relocate to new regions to open offices, then hire and train locally, ensuring that at least 15% of the workforce is now based outside India with strong teams across the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Singapore, and other markets. This, he said, is not just about growth but about “how much we are contributing back to the country where our customers are,” from building skills to running rural and tier-3 offices that keep talent closer to home. Being privately held, he added, allows Zoho to invest in R&D, rural revitalisation, and local data centres at its own pace, without pressure to chase short-term revenue or price hikes, even as some private equity–backed competitors quadruple prices to meet aggressive exit timelines.

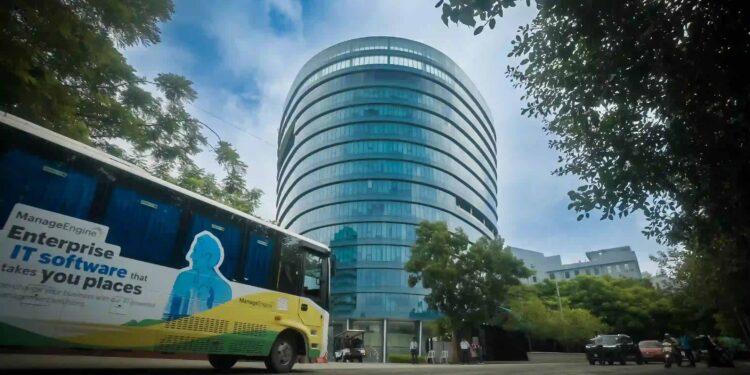

ManageEngine: From 30 customers to 90,000

For ManageEngine, Zoho’s enterprise IT management division, the 30-year story is one of repeated reinvention built on a consistent product-first ethos. Rajesh Ganesan, CEO, ManageEngine, described joining the company in 1997 as an intern and “reinventing” himself roughly every three years, mirroring how the company itself pivoted from serving a few dozen telecom backbone customers to building broadly adopted IT management software for tens of thousands of businesses worldwide. The dot-com bust of 2001, which wiped out most of Zoho’s original telecom customers, became a turning point; instead of retreating, the team used its own internal needs and the lack of affordable, simple tools as a “light bulb moment” to launch ManageEngine and target a much wider base of small and midsize businesses.

Ganesan contrasted the complexity and cost of early 2000s enterprise software—shipped on dozens of CDs and sold via lengthy, in-person sales cycles—with ManageEngine’s decision to make products downloadable from the web, backed by generous free editions and self-service trials. That “freemium before premium” approach, amplified by early use of online advertising, helped the company build what he called a truly global, channel-driven business that now counts about 90,000 paying customers across more than 190 countries and hundreds of long-standing partners. He stressed that ManageEngine’s R&D spending remains roughly double that of many competitors while its marketing spend is a fraction, reflecting a belief that “strong products are the best marketing” and that long-term resilience comes from staying close to customers and solving real operational problems, not chasing every hype cycle.

AI as infrastructure, not hype

AI surfaced throughout the event as a technology Zoho and ManageEngine treat less as a buzzword and more as infrastructure that must be engineered carefully. Speakers reminded attendees that the company has been working with AI and machine learning for more than a decade, starting in the “big data” era and evolving through classical machine learning, deep learning, and now transformer architectures and agentic systems. Rather than defaulting to large, generic models, Zoho emphasises bespoke, low-data–friendly models tuned for enterprise environments where privacy, regulation, and explainability are non-negotiable.

This philosophy is embedded in what Zoho calls “contextual AI”: hundreds of narrowly focused models woven into specific workflows—such as predicting outages from anomalous response times or flagging suspicious login patterns—without customers paying extra for AI features. The company’s AI leaders stressed that in enterprise security and IT operations, “there is no room for black boxes,” arguing that models must be able to justify their alerts and recommendations in plain, auditable terms for operators, regulators, and boards. That stance underpins initiatives such as local AI-ready data centres in Dubai and Abu Dhabi, self-hosted models that comply with regional data laws, and a “bring your own key” approach for customers who want to integrate preferred third-party large language models while retaining control.

Security, compliance, and regional futures

On cybersecurity, ManageEngine experts argued that traditional defences, static thresholds, periodic risk assessments, and purely signature-based malware detection are ill-suited to AI-enabled, identity-driven attacks and to the expanding digital attack surfaces across smart cities and national projects. They pointed to the rise of “non-human identities” such as service accounts, APIs, sensors, and AI agents, estimating that there may already be 80 such identities for every human user, many of them unmanaged or orphaned. This, they warned, creates new pathways for attackers to move laterally, impersonate trusted systems, and silently interfere with operations in sectors ranging from logistics to energy and digital twins.

Compliance leaders from Zoho framed regulation not as a burden but as an ongoing discipline woven into business objectives, training, and design, especially as regions like the GCC tighten data residency and privacy expectations. The company’s decision to avoid monetising customer data, strip out third-party trackers from its own sites, and keep AI models “privacy by design” was presented as both an ethical stand and a strategic differentiator in markets where trust is increasingly a competitive asset. Across sessions focused on the Middle East, speakers linked these choices to national ambitions—from Saudi Vision 2030 to UAE digital strategies—arguing that resilient cyber architecture, explainable automation, and local skills will be critical as regional enterprises become fully digital by default.

Transnational localism in practice

Throughout the event, the narrative focused on Zoho’s philosophy of building global products while remaining locally grounded in where it hires, where it builds offices and data centres, and whom it chooses to serve. Davey pointed to rural offices in India, Mexico, and the United States as examples of “structural efficiency,” arguing that moving to tier-3 and tier-4 towns allows Zoho to lower costs, reduce urban migration pressures, and invest more in R&D and customer value instead of rent. Ganesan echoed this by noting that Zoho deliberately planted offices in less obvious locations around the world, including secondary cities, as a way to ensure that regions like India, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East are not merely markets but talent and innovation hubs in their own right.

The result, as the 30-year milestone made clear, is a company that sees its next decade less in terms of valuation or exits and more in terms of staying power: building AI that is explainable and cost-conscious, cybersecurity that can keep pace with machine-speed threats, and enterprise IT platforms that remain affordable, transparent, and rooted in the communities they serve.

Discussion about this post